|

“Using Financing to Unleash the Power of Franchising in the Social Sector” Will Feature Engaging Content to Help Social Franchises Grow Efficiently and Sustainably in Today’s Challenging Environment.

Video recordings of this event now available here (WASHINGTON, D.C.) Sept. 11, 2020 -- The Rosenberg International Franchise Center at the University of New Hampshire and the International Franchise Association's (IFA) Social Sector Committee will host a virtual conference, “Using Financing to Unleash the Power of Franchising in the Social Sector,” on Oct. 28, 2020, from 10 a.m. – 2 p.m. ET. The free event will convene a diverse group of social sector and commercial franchisors and franchisees, social impact investors and donors, franchise experts and consultants, and other thought leaders and scholars from around the world to discuss best practices for using the variety of financing options available to help social franchises grow efficiently and sustainably in today’s challenging environment. Speakers will include:

“Social sector franchising creates opportunities for local entrepreneurs to deliver a variety of products and services to underserved communities worldwide, while creating much-needed jobs,” said Marla Rosner, Chair of the IFA Social Sector Committee and Senior Learning & Development Consultant at MSA Worldwide. “Amid the COVID-19 pandemic, it’s now more critical than ever to bring together leaders in social sector and commercial franchising to discuss how we can support the important work of social franchises and their continued growth. We invite anyone interested in social franchising to join us for this virtual conference.” “We are excited to partner with IFA’s Social Sector Committee to organize this important event,” said Dr. Hachemi Aliouche, Director of the Rosenberg International Franchise Center. “Using a multi-disciplinary approach to focus on the critical issue of financing the launch and development of social franchises, this virtual conference brings together leaders from a variety of sectors involved in social franchising. It will help identify key challenges and promote best practices for the advancement of the social franchising field.” For more information about the event and to register, visit https://www.unh.edu/rosenbergcenter/2020-unhifa-virtual-conference-social-sector-franchising. About the Rosenberg International Franchise Center Named for franchise pioneer William Rosenberg, the Rosenberg International Franchise Center (RIFC) explores and advances the understanding of franchising through research, education, and outreach. RIFC is an international center of excellence on franchise finance, international franchising, and social franchising. It is noted for its three indices: the RIFC 50 Index, which tracks the financial performance of 50 public franchisors representative of the US franchise sector; the RIFC International Franchise Attractiveness Index, which ranks 131 countries according to their attractiveness as international franchise expansion markets; and the RIFC Global Social Franchise Index, which ranks 131 countries according to the impacts social entrepreneurship and social franchising can have on the well-being of their citizens. For more information, visit https://www.unh.edu/rosenbergcenter/. About the IFA Social Sector Committee The Social Sector Committee was first established by the International Franchise Association (IFA) in 2009 as a Task Force, to provide a platform to advance and leverage the use of commercial franchising methods and technology to serve the needs of the social franchising community. It was founded by Michael Seid, founder and Managing Director of MSA Worldwide and former member of the IFA Board of Directors. The Committee is composed of leading franchisors, franchisees, and professionals in commercial franchising whose goal is to help social sector franchisors and other NGOs become more effective and efficient in achieving their goals through the principles of franchising. For more information, visit http://www.socialsectorfranchising.org. About the International Franchise Association Celebrating 60 years of excellence, education, and advocacy, the International Franchise Association is the world's oldest and largest organization representing franchising worldwide. IFA works through its government relations and public policy, media relations and educational programs to protect, enhance and promote franchising and the more than 733,000 franchise establishments that support nearly 8.4 million direct jobs, $787.5 billion of economic output for the U.S. economy and 3 percent of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP). IFA members include franchise companies in over 300 different business format categories, individual franchisees, and companies that support the industry in marketing, law, technology, and business development. # # # Top Professionals in the Franchising Community Donate Time to Help Entrepreneurs Grow Using Franchise Methods (WASHINGTON, D.C.) March 27, 2020 -- The International Franchise Association’s (IFA) Social Sector Task Force has launched a mentorship program to help entrepreneurs leading environmental enterprises grow their organizations leveraging methods used in the franchise business model.

The IFA Social Sector Task Force is seeking entrepreneurs with existing businesses focused on one or more of the following sectors to join its new mentoring program: solar power and electric grids, clean water, sanitation systems, food waste management, agriculture, transportation, and recycling. “Social sector franchising creates opportunities for local entrepreneurs to deliver a variety of products and services to underserved communities worldwide, while creating much-needed jobs. The Task Force’s goal is to bring together leading franchisors, franchisees, and suppliers and leverage their expertise in commercial franchising to help social sector concepts grow more efficiently and sustainably,” said Marla Rosner, chair of the IFA Social Sector Task Force and Senior Learning and Development Consultant at MSA Worldwide. Over the last 10 years, members of the IFA Social Sector Task Force have mentored a variety of social enterprises around the globe, sharing their knowledge of and expertise in everything from franchise system management and development, to consumer marketing, training, operations, business analytics, legal and financial services, pricing strategies, and more. In 2017, the co-founders of WSV — an organization that helps entrepreneurs establish pre-designed and highly impactful community run businesses — worked with the IFA Social Sector Task Force address their challenges, including shortening the lengthy timeline for launching new partnerships with NGOs. “Since participating in the Task Force’s mentoring program, WSV has grown multiple social sector concepts to offer to NGOs to franchise in their communities,” said co-founder Adam Boxer. “We used the Task Force’s expertise in franchising to do a deep dive into all the different areas of our business — looking at franchising, law, funding, and documentation — to identify holes and areas we should be looking at that we haven’t thought of. As a result, we discovered loads of things to develop.” Entrepreneurs interested in applying for the IFA Social Sector Task Force’s mentoring program can contact Lori Kiser at Lori@LoriKiser.com. For more information on the Task Force or for IFA members interested in becoming a mentor, visit http://www.socialsectorfranchising.org. About the IFA Social Sector Franchising Task Force The Social Sector Franchising Task Force was established by the International Franchise Association (IFA) in 2009 as a platform to advance and leverage the use of commercial franchising methods and technology to serve the needs of the social franchising community. It was founded by Michael Seid, founder and managing director of MSA Worldwide and former member of the IFA Board of Directors. The Task Force is composed of leading franchisors, franchisees, and professionals in commercial franchising whose goal is to help social sector franchisors and other NGOs become more effective and efficient in achieving their goals through the principles of franchising. For more information, visit http://www.socialsectorfranchising.org. About the International Franchise Association Celebrating 60 years of excellence, education and advocacy, the International Franchise Association is the world's oldest and largest organization representing franchising worldwide. IFA works through its government relations and public policy, media relations, and educational programs to protect, enhance and promote franchising. IFA members include franchise companies in over 300 different business format categories, individual franchisees, and companies that support the industry in marketing, law, technology and business development. # # # Contact: Marla Rosner MSA Worldwide (415) 225-8607 mrosner@msaworldwide.com IFA Chair Catherine Monson has appointed Marla Rosner, Senior Learning and Development Consultant at MSA Worldwide, to be the new Chair of the IFA’s Social Sector Franchising Task Force. Marla has served in the role of Task Force Manager since 2012. Under her leadership the group has developed a Mentoring Program, which matches IFA members who want to share their knowledge of and experience in franchising with social sector franchisor management and franchisees. Michael Seid, Managing Director of MSA Worldwide, and founder and outgoing Chair of the Task Force, has been appointed Chair Emeritus of the Task Force to recognize his outstanding efforts in the area of social sector franchising. As an experienced commercial franchise expert with established social franchise expertise, he works with established social franchisors to improve their performance, with NGOs to explore their franchising opportunities, and with donors to maximize the use of the funds they provide in Low and Middle Income Counties (LMICs). Peter Holt, CEO of The Joint Chiropractic and Task Force contributor since 2014 will assume the role of task force Vice Chair. About the IFA Social Sector Franchising Task Force The Social Sector Franchising Task Force was established by the International Franchise Association (IFA) in 2009 as a platform to advance and leverage the use of commercial franchising methods and technology to serve the needs of the social franchising community. It was founded and first chaired by Michael Seid, founder and managing director of MSA Worldwide and former member of the IFA Board of Directors. The Task Force is composed of leading franchisors, franchisees, and professionals in commercial franchising whose goal is to help social sector franchisors and other NGOs become more effective and efficient in achieving their goals through the principles of franchising. In addition to mentoring programs the Social Sector Franchising Task Force offers peer groups for social franchisor management, well articulated FAQ’s on it’s website and a guide for attorneys and consultants who may be assisting social franchisors in establishing their franchise systems. For more information, visit http://www.socialsectorfranchising.org. About the International Franchise Association Celebrating 60 years of excellence, education and advocacy, the International Franchise Association is the world's oldest and largest organization representing franchising worldwide. IFA works through its government relations and public policy, media relations and educational programs to protect, enhance and promote franchising. IFA members include franchise companies in over 300 different business format categories, individual franchisees and companies that support the industry in marketing, law, technology and business development. # # #  Learn how to put your franchise experience to use in helping social enterprises expand using franchising methods. The IFA Social Sector Franchising Task Force will be meeting at the IFA Convention on February 27th, 8:00-9:45 a.m. in Las Vegas at the Mandalay Bay Resort, Breakers Room L. Unable to attend but interested in learning more? Read our FAQs! Want to mentor or be mentored? Contact Marla Rosner at mrosner@msaworldwide.com See an example of who we have mentored, here. By Joyce Mazero | Franchising.com

As noted in my previous article (Social Impact Investing Shows Up in International Social Franchise Programs), there are many examples of how social impact investment has facilitated the use of the social franchise model - permitting social/micro-franchisors and franchisees to scale their businesses, allowing them to employ local residents, serve more customers, and improve the economic health of local communities in an international context. In the U.S., there is compelling evidence of interested parties having examined the feasibility of using the business format franchise model in low-income communities on a "for-profit basis" to 1) reduce the leakage of employment and buying power to surrounding communities, while 2) building an economically beneficial business presence in the local market. In this article, I report on some of the case studies, evaluations, and programs supporting this premise. There is sufficient evidence of franchises that can fill the gap between existing businesses and the lack of healthy food, retail, fitness, and basic business services in demand in underserved local markets. There also are examples of franchisors who have unilaterally implemented programs facilitating the training and qualifying of employees interested in becoming franchisees. In the U.S., there appears to be little reported and accessible evidence of how low-income communities, impact investors, universities, government agencies, and franchisors have worked together in markets to bring trained and qualified local entrepreneurs the opportunity to operate franchised businesses in the areas so in need of attention. More specifically, there appears to be a lack of evidence of 1) how finding, paying for, and maintaining resources to support the training and eventual qualifying of a local entrepreneur can be allocated and shared among the franchisor, community developers, impact investors, universities, and government agencies; and 2) how that revenue can be allocated and shared among the same parties in a fully "for-profit" environment. I hope the examples in this article will act as a catalyst to cause further engagement in building a shared network of resources to foster and scale programs that result in trained, qualified local operators in low-income and under-developed markets in the U.S. Boston's Neighborhood Restaurant Initiative In an effort to revitalize low-income or commercial areas, the City of Boston launched the Neighborhood Restaurant Initiative in 2004. The initiative, which included locally owned franchised businesses, focused primarily on developing full-service sit-down restaurants in neighborhoods lacking access to them. The initiative, which provided resources for developing new and expanding full-service restaurants included technical assistance (creating business plans, choosing a location, marketing); permitting and licensing; design assistance (signage, logos, and storefronts); facade improvement grants; liaisons to city departments; financing (direct assistance and referrals); and workshops for potential restaurant entrepreneurs. The initiative also provided additional funding as a junior loan for qualifying businesses. Chick-fil-A's employee development programs Despite remaining closed on Sundays and facing national public relations controversies in the past few years, Chick-fil-A has continued to scale successfully, exhibiting tremendous market share growth in the limited-service chicken segment. Chick-fil-A is known to focus on a long-term, holistic approach to supporting employees that includes core values and team member training and development. The company's Remarkable Futures Scholarship program directs a portion of its proceeds to annual scholarships for employees to attend colleges and universities. Every employee that qualifies receives a pre-determined amount of scholarship money. Since the program's inception in 1973, Chick-fil-A has given more than $34 million in scholarship money to 34,000 employee team members. Chick-fil-A also offers the Jumpstart Experience leadership development program, an intensive job opportunity and personal development program that gives employees a "jump start" in their business careers. This program requires that participants have graduated from a four-year college and have exhibited at least two years of leadership experience. Each participant undergoes a demanding, 30-month program that includes hands-on experience in running all facets of a company restaurant, individual mentorship opportunities, and life-planning assistance. B. Good: How a smaller brand can offer local economic benefits B. Good is a regional all-natural burger and sandwich franchise restaurant network operating in Massachusetts, Maine, New Hampshire, New Jersey, Rhode Island, North Carolina, and Connecticut. Its menu features locally sourced seasonal ingredients for all of its beef and produce. The franchise's costs do not appear to be significantly higher than regular, non-locally sourced fast food restaurants because the company uses whole food products and prepares the products on site. The company also focuses on building networks with a growing list of local farmers and plugging them directly into their supply chain. To maintain a unique list of ingredients and products in the face of obvious sourcing challenges, B. Good has a limited menu with a reduced number of offerings, compared with other fast food restaurants. Its flexible menu highlights ingredients unique to each franchisee's local market. While B. Good does not have the geographic presence or numbers of a Chick-fil-A, the company is interesting because of its flexibility, and provides a good example of how franchises, although in a smaller network, can offer the same local economic benefits as independently owned businesses and larger franchised chains. Domino's "Deliver the Dream Program" Domino's "Deliver the Dream" program provides financial support and technical assistance to Domino's minority team members who desire to become franchisees. The program identifies and develops high-performing, elite minority team members regardless of where they began with the company. Domino's also partners with outside resources to facilitate financial assistance for selected members. This partnership has allowed participants to start franchises with a significantly reduced franchise fee. Domino's offers several other programs that serve as feeders for this program, including optional training programs for employees interested in becoming managers; and the Franchise Management School for employees interested in becoming franchisees and operating managers. Next time: Social impact investing in Georgia's Hollowell Parkway Corridor and the public-private partnerships making it happen. Joyce Mazero, a shareholder with Polsinelli PC, a law firm with more than 825 attorneys in 21 offices, is co-chair of its Global Franchise and Supply Network Practice. Contact her at 214-661-5521 or jmazero@polsinelli.com. The International Franchise Expo comes to the Javits Center in New York, NY from May 31 through June 2, 2018! Enjoy free registration courtesy of MSA Worldwide through this link: free Expo registration (use promo code MSA when registering).

On Thursday May 31, Michael H. Seid, Managing Director of MSA Worldwide, will host a presentation on how the use of commercial franchise techniques is being used in social franchising to improve the delivery of social services and products at the Base of the Pyramid. Three social franchise initiatives will be explored: CFWshops in Kenya, Woman360 in Ghana, and Ohio State University's Global Water Initiative in Tanzania. In addition, Mr. Seid will explore why companies like KFC are expanding in Kenya and throughout Africa. All social franchise or commercial franchise questions the audience may have will be addressed. Presentation details:

To attend this presentation, please RSVP directly to:

For a full schedule of the 2018 International Franchising Expo, visit www.ifeinfo.com.www.ifeinfo.com/ Many IFA members have expressed interest in social franchising, the application of the franchise model towards humanitarian ends. IFA's 2018 Convention offers a number of opportunities to learn about social franchising and begin to engage.

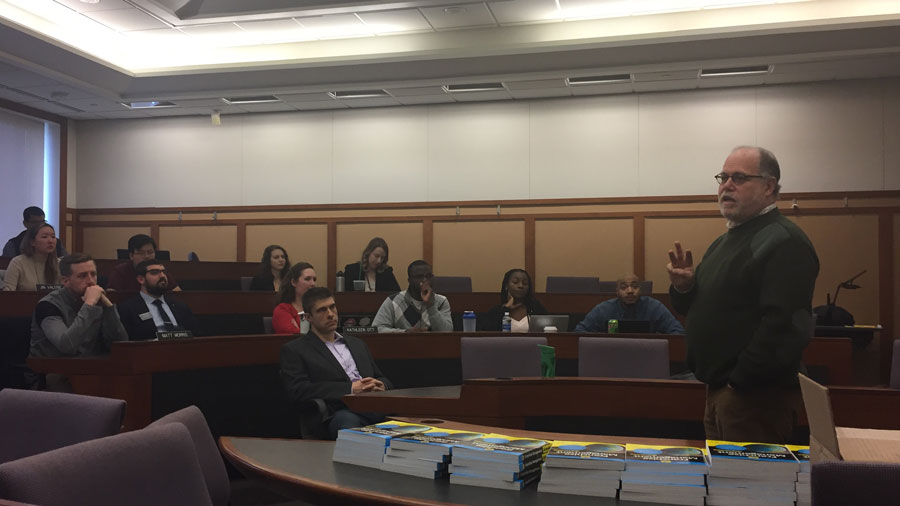

1. IFA Franchising in the Social Sector Task Force Meeting 10 am to Noon, Saturday, February 10th Phoenix Convention Center Room North 227-B-C 2. How Social Franchises Are Addressing Complex Problems in the Developing World 8:30 to 10 am, Sunday, February 11th Phoenix Convention Center Room North 123 This interactive panel and audience discussion will examine commercial franchise approaches to complex issues in the developing world. The issues faced by Ohio State University's Global Water Institute in reestablishing well water, local delivery and seasonality issues in Tanzania are unique and difficult. Franchising instead of a classic NGO model was chosen because of the promise of consistent quality and sustainability. The structure of the Global Water Institute (GWI) franchise offering and approach will be examined. In this session, the audience, based on their experience in commercial franchising will be challenged to look at the issues GWI is facing and recommend changes to their adopted strategy. Moderator: Michael Seid, CFE, Managing Partner, MSA Worldwide Speaker: Marty Kress, Executive Director, Global Water Institute, The Ohio State University Speaker: Mark Vanase, Director, Field Operations, ServiceMaster Restore 3. Business Solutions Roundtable- Social Franchising: Serving the Base of the Pyramid 8:00 to 9:45 am, Tuesday, February 13th Phoenix Convention Center, Room West 301 B-D Table 27 Facilitators: Michael Seid, CFE, CFW Shops & Ferenz Feher, Feher & Feher Check out your personal agenda and register today at https://www.franchise.org/convention. Visit the IFA Social Sector Task Force's site to learn more: http://www.socialsectorfranchising.org/about.html What is social franchising? Commercial franchising and social franchising are variations on the same basic strategy for expanding a business. They differ in just two ways: » The type and purpose of the products and services offered by the business being franchised » The profile of the target customer Social franchised businesses, like those operated by traditional NGOs (nongovernmental organizations) are primarily developed to offer products and services that people need - not simply want - such as healthcare, safe drinking water, sanitation, clean energy, and education. These are social enterprises whose creation is targeted to achieve goals such as those set in the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals established by the United Nations (https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/sdgs). With the exception of the different profile of the targeted consumer, social sector franchises and commercial franchises are quite similar. In contrast to the customer who walks into a McDonald's or a Marriott, the consumer targeted by social franchise systems often can't afford to pay the entire cost of the goods and services they need. Because of that, social franchisors are usually unable to generate the royalty and other revenue and fees necessary to independently sustain the overall business. Being independently sustainable is the hallmark of commercial franchising. That is the significant difference between social and commercial franchisors. Recently, a member of our external advisory board, Michael Seid, international franchising consultant, came to speak to a group of Fisher MBA students on campus. Well over 40 students attended the lecture, on a topic of great interest in the business world: franchising. Franchising is defined as licensing the right to use a firm’s business model and brand for a prescribed period of time, and Seid is definitely an expert in the practice. The co-author of Franchising For Dummies (co-written with the late Dave Thomas, founder of Wendy’s), as well as co-author of a book released this year, Franchise Management for Dummies, he has spent much of his life working in the world of franchising as a consultant.

At Fisher, Seid shared his insight and expertise on various aspects of franchising, but one topic that many of the students that attended the session enjoyed very much was social franchising. Social franchising takes a new spin on the model you might recognize from the fast-food world. The difference is that instead of businesses providing just consumer products or services, social franchise systems provide public-oriented services like health care or water in an entrepreneurship/non-profit hybrid model that can be replicated just like a restaurant chain. In particular, Seid discussed a group of birthing centers that he and his partners have helped to launch in Ghana. The centers use a hub-and-spoke model where locally deployed clinics are owned and operated by nurses or midwives, and focus on prenatal care, but a master franchiser operates centrally-located hub clinics to which mothers can travel to give birth or if they need more advanced care. The master franchiser also provides business support and assures strict adherence to brand standards, delivering a high-quality and standardized experience to expectant mothers. While this network of birthing centers is new and results aren’t yet in, if the social franchising model Seid and his colleagues have used for medical clinics in Kenya and Rwanda are any indication, the result will be better quality service with lower fees than government-operated centers. “I’ve always had an interest in applying a business model into expanding free health clinics, so I found this information very useful,” said one MBA student who attended the talk. “It’s amazing how so many different people can seamlessly adapt a business model for the overall growth of the organization.” GWI’s External Advisory Board members Michael Seid and Tom Blackstock (a former Coca Cola executive) have collaborated with Fisher faculty member Keely Croxtonand others on the GWI team (including several cohorts of Fisher MBA students) to develop a social franchising model for water services in rural parts of developing countries. The model aims to use market mechanisms to help villages keep newly established or rehabilitated water systems working for the long-term, something that has been a failure point for many water philanthropy projects in the past. A version of the model will be rolled out in two villages in Tanzania partnering with GWI to launch pilot Sustainable Village Water Systems this fall. Presented by Bill Maddocks, MSCED, Carsey School of Public Policy, University of New Hampshire Access the webinar here: https://www.franchise.org/file/sstf-bill-maddocks-nov-28-17mp4

IFA Social Sector Task Force webinar presented by Dr. Fiona Wilson, University of New Hampshire  Access the webinar here:

https://www.franchise.org/file/ifa-sstf-beyond-social-sector-franchisingmp4 |

Blog Team

Posts on our blog are contributed by a team of professionals dedicated to developing valuable resources for the Social Sector Franchising community. Archives

March 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed