|

The promise of social franchising to deliver sustainable solutions to society’s social needs is grounded in the fundamental principles that have made franchising such a successful replication model in the commercial sector. Unfortunately, most social franchise implementers are not familiar enough with those principles to optimize franchising’s potential. This article is intended to shed light on the key conditions that all implementers should be aware of when designing or striving to improve a social franchise.

It will also be useful for funders of social franchisors to be aware of these conditions so that their investments are supporting best practices and driving the field of social franchising toward a more impactful and sustainable future. Conditions Required for a Social Franchise to SucceedSocial franchising will deliver results, just like commercial franchising delivers results, when certain conditions are in place. These are[1]:

When all of these conditions are in place, it is safe to conclude that the concept is franchisable. The next step would then be to design the franchise. Elements of Good Social Franchise Design Once the groundwork for success is laid by creating the conditions described above, the franchise can be designed. Following are some key elements of all good franchise designs that should be addressed when designing or strengthening a social franchise system.

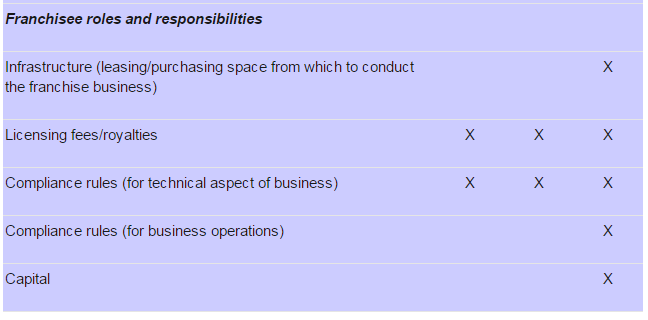

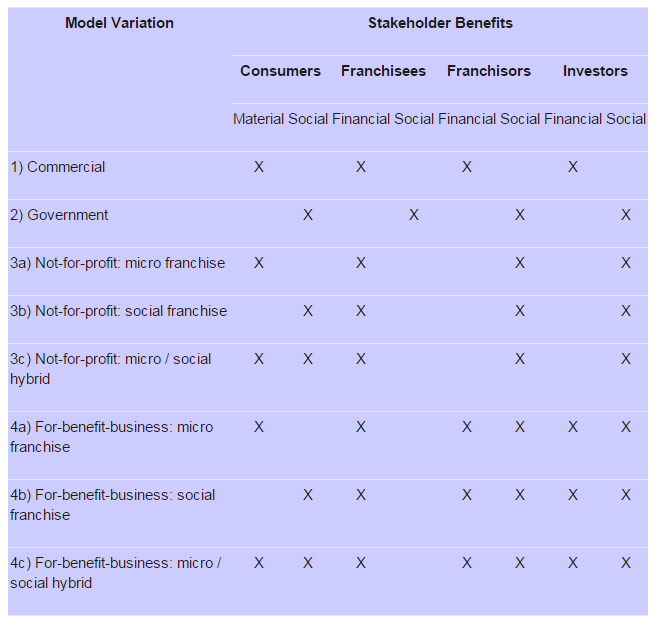

ConclusionImplementers and funders of social franchising will dramatically improve their bottom lines when they understand the fundamentals of franchising discussed in this article. There are experts in the field of franchising that can help with both design and execution of social franchises in the same way that they help commercial businesses. The International Franchise Association’s Social Sector Task Force has established a mentor program, and consulting firms like MSA Worldwide offer highly specialized technical support in social franchising. Whether a social business considering expansion through franchising, or an NGO that has been operating a franchise and is looking to improve its performance, there are resources available to help implementers make smart design decisions that will enable them to achieve social and financial goals. In the end, while many parties benefit from a well-designed social franchise, those who stand to benefit most are the people in need of the products and services being franchised. It behooves us all to make the effort to learn from each other so that we can better serve those in need and make this world a better place. [1] Seid, Michael and Thomas, Dave; Franchising for Dummies, 2nd Edition, Wiley Publishing, Inc., 2010. Differentiating commercial, micro, social, and hybrid franchise models By Julie McBride, Senior Consultant Social Franchising, MSA Worldwide Getting on the same page Put simply, franchising is a method of replicating a proven business. Franchising has two main forms. In Product/Trade Name Franchising (Traditional Franchising), a franchisor owns the right to a name or trademark, licenses the right to use that name or trademark, and generally provides the franchisee with a product that needs pre- and post-sales service. Business Format Franchising involves a more complex relationship in which the franchisor provides franchisees with a full range of services and support, and the franchisee operates according to the franchisor’s standards in delivering the branded products or services to consumers. While Traditional Franchising is larger is total sales, Business Format Franchising has become one the most widely used methods for expanding the distribution of proven business concepts (Alon, 2014). There are now hundreds of industries using franchising to distribute products and services including restaurants, hotels, cleaning services, fitness centers, assisted living, and home health care. According to the IFA, franchising is growing rapidly overseas with more than 400 U.S. franchise systems operating internationally. There is also an emergence of marginalized segments of society, particularly women and minorities, operating franchise businesses. Franchising is a desirable growth strategy to the concept owner because it allows them to grow at a high rate while maintaining brand standards. It also reduces the amount of growth capital that the franchisor must raise. Franchisees benefit from gaining access to proven concepts and business systems, and because most franchisors offer ongoing training and support and in some cases financing assistance, franchising provides a way to overcome the most common obstacles to starting a business - lack of business experience, and insufficient start up capital (Harrington, 2013). Franchising has taken many forms over the years as it has adapted and evolved to meet changing market needs. Social and micro franchising are the latest concepts in franchising, and interest in using them to deliver benefits to underserved communities in both developed and developing economies is gaining momentum (Alon, 2014). The purpose of this article is to provoke discussion around ways in which the social and micro franchising communities of practice can organize and compare information and ideas so that the field of practice can advance more rapidly. This article will be followed by a series of case studies that highlight lessons learned about the different types of models, and circumstances where each would be appropriately adapted. Overcoming a critical obstacle to progress As new model variations emerge, there is a need to understand their effectiveness and applicability to different contexts so that they can be replicated appropriately. However, the field of social franchising is growing so haphazardly that it is challenging to capture best practices and lessons learned, let alone use them to advance the field. It is therefore difficult for stakeholders to make informed decisions about franchise design and investment. The result is that funding is not always channeled to effectively designed franchise systems. When poorly designed and/or executed franchises are assessed and compared without understanding how they are fundamentally flawed or different from each other, erroneous conclusions are drawn about the effectiveness of franchising as a business model (as opposed to the effectiveness of the organization attempting to use the business model). As a result, funds for social franchising in general could be reduced or discontinued and end up unnecessarily shortening the lifespan of a model that has tremendous potential to improve people’s lives. The first step to solving the challenges ahead is not as sexy as the title of this article suggests. It is simply a matter of defining, identifying, and differentiating between the various “shades,” or variations, of franchising. Once that is done, a social and micro franchise community of practice can work more productively together using a common understanding and language around franchising. Looking a little closer: variations of franchise models Box 1: Definitions of Commonly Used Franchise Models Franchise: A relationship, as defined by the FTC and various states, which typically includes three basic elements: (1) the granting of the right to use the systems mark, (2) substantial assistance or control provided by the franchisor to the franchisee, (3) the payment of a fee (in excess of $500) during a period of time six months before or six months following the commencement of the relationship (Seid, 2015). Traditional Franchise (aka “Product and Trade Name Franchise”): The licensing of a franchisee/dealer to sell or distribute a specific product using the franchisor’s trademark, trade name and logo. (Automobile dealerships, Truck dealerships, Farm equipment, Mobile homes, Gasoline service stations, Automobile accessories, Soda, Beer, Bottling are types of traditional franchising. In traditional franchising the franchisee generally is required to provide presale or post-sale services of the franchisor’s products. Describes the specific product or service associated with the delivery, not the system of delivery as in Business Format Franchising.) (Seid, 2015). Fractional Franchise: The products or services being franchised are housed within an existing business and contribute to only a portion of overall revenues. Business Format Franchising (BFF): A franchise occurs when a business (the franchisor) licenses its trade name (the brand) and its operating methods (its system of doing business) to a person or group (the franchisee) that agrees to operate according to the terms of a contract (the franchise agreement). The franchisor provides the franchisee with support and, in some cases, exercises some control over the way the franchisee operates under the brand. In exchange, the franchisee usually pays the franchisor an initial fee (called a franchise fee) and a continuing fee (known as a royalty) for the use of the trade name and operating methods. BFF describes the system of delivery, not the specific product or service associated with the delivery as in Product or Trademark Franchising (Seid, 2015). Social Franchise: The application of commercial franchising methods and concepts to achieve socially beneficial ends” (International Franchise Association’s Social Sector Task Force, 2014). Social Franchising is used to increase access to products and services across a range of socially oriented industries (e.g., education, health, agriculture, water, sanitation, clean energy), with its target market being underserved populations in low, medium, and high-income countries around the globe (MSA Worldwide). Micro Franchise: A small business whose start up costs are minimal and whose concepts and operations are easily replicated (Fairbourne et. al, 2006). Micro franchising is used to increase access to business opportunities that enable people to lift themselves out of poverty. Its primary purpose is economic development and unlike social franchising, it is not necessary that the business being franchised meet consumer social needs (MSA Worldwide). Hybrid Social/Micro Franchise: A micro franchise of a business that delivers social benefits to consumers. What all of these models have in common is that they offer franchisees a brand and products that represent value to the consumer. Fractional and business-format models offer services in addition to products. Because service delivery relies on human behavior, maintaining standards across the network for these models requires more inputs such as training and ongoing support from the franchisor. A rigorous compliance system is also required to maintain control over the brand. As the franchise becomes more central to the franchisee’s business success, the franchisor will have more control over franchisee quality and consumer brand perception. This is because franchisees value the franchise offering enough to deter them from behaving in ways that would risk losing franchise rights. Fractional franchises, where only a portion of the franchisee’s business is dependent upon support from the franchisor, are more difficult to control and require much greater effort on the part of the franchisor to maintain service standards. Further, it is doubtful in a social franchise that the franchisor will be able to recover a significant portion of operating costs through franchisee fees or royalties and thus achieve sustainability when the financial value-add to the business is small or even unmeasurable, as is the case with most fractional social franchises. While these are significant potential pitfalls of fractional franchising, the model does meet the needs of social franchisors in terms of reducing the amount of start up capital required - since the model is adding to existing businesses rather than creating new ones (Alon, 2014). Figure 1, below, provides a high-level overview of each model’s features and the complexity of the franchisor/franchisee relationship in terms of their roles and responsibilities to each other. Knowing the differences will help stakeholders understand why different models out-perform each other in different ways, and help them select models that are suited to achieving their goals. Figure 1. Defining and Differentiating Features of Common Franchise Models The devil is in the details |

Blog Team

Posts on our blog are contributed by a team of professionals dedicated to developing valuable resources for the Social Sector Franchising community. Archives

May 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed